Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

This week, we cover Margaret St. Clair’s “The Man Who Sold Rope to the Gnoles,” first published in the October 1951 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. You can find it in The Weird, among other collections. Spoilers ahead.

“Judging from his appearance, the gnole could not safely be assigned to any of the four physio-characterological types mentioned in the Manual; and for the first time Mortensen felt a definite qualm.”

Mortensen is a go-getter, eager for a special mention from the district manager at the next sales-force meeting. So, despite knowing their bad reputation, he decides to sell rope to the gnoles. Surely they have an unsatisfied want for cordage, and what they might do with it is none of Mortensen’s business.

The night before his sales call, Mortensen studies the Manual of Modern Salesmanship, underlining the qualities of an exceptional salesman. He notes the need for physical fitness, charming manner, dogged persistence, unfailing courtesy, and high ethical standards. Somehow, though, he overlooks the imprecations toward tact and keen observation.

Buy the Book

Star Eater

The gnoles live on the edge of Terra Cognita, on the far side of a dubious wood. No path leads to their high narrow house, but Mortensen tracks them by their smell. The gnoles watch him arrive through holes in trees. That he knocks on their door confuses them—no one’s done that for ages!

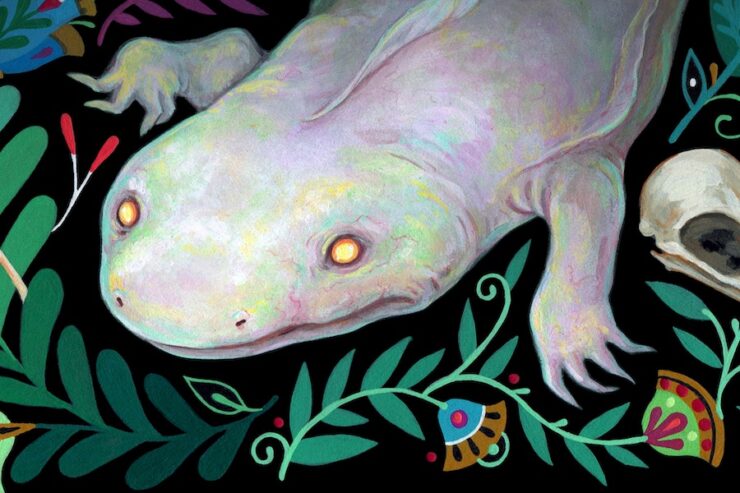

The senior gnole answers the summons. He resembles a rubbery Jerusalem artichoke, with small red eyes faceted like gemstones. Mortensen bows politely and launches into his sales talk. But before he can enumerate the varieties of cordage that his firm manufactures, the gnole turns his head to demonstrate his lack of ears. Neither can his fanged mouth and ribbony tongue accomplish human speech. Mortensen feels a definite qualm. Nevertheless, knowing a salesman must be adaptable, he follows the gnole inside.

The parlor features fascinating whatnots and cabinets of curiosities. Shelves display emeralds big as a man’s head, from which all the light in the dim room emanates. Deprived of his prepared sales talk, Mortensen proceeds to demonstrate the cordages in his sample case and write out their attributes and prices on an envelope.

He lays out henequen cable, ply and yarn goods, cotton and jute twines, tarred hemp, and a superlative abaca fiber rope. The senior gnole watches intently, poking the facets of his left eye with a tentacle. From the cellar comes an occasional scream.

Mortensen soldiers on, and finally the gnole settles on an enormous quantity of abaca fiber rope, evidently impressed by its “unlimited strength and durability.” Mortensen writes up the gnole’s order, brain on fire with triumph and ambition. Surely the gnoles will become regular customers, and after them, why shouldn’t he try the gibbelins?

Learning the terms of sale are thirty percent down, the balance upon receipt of goods, the senior gnole hesitates. Then he hands Mortensen the smallest of the wall-displayed emeralds—a stone that could ransom a whole family of Guggenheims! Sales ethics forbid Mortensen to accept this excessive down-payment. Regretfully he hands back the emerald and scans the room for a fairer payment. In a cabinet he spots two emeralds the size of a man’s upper thumb joint—these should do nicely.

Unfortunately, Mortensen has chosen the senior gnole’s precious auxiliary eyes. A gnole would rather be a miserable human than have a vandal touch his spare eyes! Too elated to see the gnole stiffen or hear him hiss, Mortensen takes the twin emeralds and slips them into a pocket, all the time smiling (charmingly, as per the Manual) to indicate that the little gems will be plenty.

The gnole’s growl makes Mortensen abandon both elation and dogged persistence, and run for the door. Tentacles as strong as abaca fiber bind his ankles and hands, for though the gnoles might find rope a convenience, they don’t need it. Still growling, the senior gnoles retrieves his ravished eyes and carries Mortensen to the fattening pens in the cellar.

Still, “great are the virtues of legitimate commerce.” The gnoles fatten Mortensen up, then roast and eat him with real appetite; uncharacteristically they refrain from torturing him first, and slaughter him humanely. Moreover, they ornament his serving plank with “a beautiful border of fancy knotwork made of cotton from his own sample case.”

What’s Cyclopean: All authorities unite in describing the woods on the far side of Terra Cognita as “dubious.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Good modern salespeople treat all potential customers as equals. The reverse, unfortunately, is not necessary true.

Weirdbuilding: The prime authority on gnoles has attested to their artful customs—that would, presumably, be Lord Dunsany.

Libronomicon: The Manual of Modern Salesmanship can tell us many important things. Unfortunately, it doesn’t address the details of handling more… unusual… consumers.

Madness Takes Its Toll: No madness this week, aside from an extremely angry senior gnole.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

If you’re fascinated by the stranger corners of reality, you might choose to go into weirdness as a career. Mulder and Scully get paid to document Things Man Was Not Meant to Know, and many R&D companies understand the value of a good mad scientist. Independently wealthy dilettantes can delve into whatever questions catch their fancies, no matter how dangerous. Authors, of course, are never safe. But in a world where incomprehensible immortal entities with only a tangential interest in the well-being of humanity plaster their logos on every available surface, even the most seemingly ordinary job can intersect with the uncanny. Advertising, for example, or finance.

Or sales. Knock on enough doors, and you might knock on the wrong one—accidentally or, with enough motivation from the district sales manager, on purpose. So it goes for Mortensen. Why not sell to the gnoles? The Manual of Modern Salesmanship, after all, assures us that all people/entities are basically alike. Same basic motivations, same basic desires, and the same basic shpiel should work if offered with sufficient charm…

Mortensen’s not put off his game when the Senior Gnole turns out to lack ears or means to speak aloud. It’s hardly an unprecedented situation among humans, after all—presumably he’s capable of an unfazed demo in a Deaf household as well, and good for him. But a sales manual written after 1951 might also have pointed out that cultural differences can, in fact, matter a great deal beyond the surface details of communication. And might perhaps also included the key advice, “Do not haggle with gnoles, for you are crunchy and taste good with ketchup.”

Another of Mortensen’s failures goes unmentioned, but in 1951 might not have needed explicit mention to attract readers’ notice. That would be his disinterest in how his customers plan to use his goods, a disinterest that continues even through all that screaming in the background—though presumably he becomes much more interested later. (Insert comment here about the personal safety assumptions of people who sell utensils to face-eating leopards.)

Dunsany—prime authority on gnoles—chose to keep his descriptions sparse. “How Nuth Would Have Worked His Art…” is built from negative space and fill-in-the-fear. All we learn of gnoles from Dunsany is their fondness for that keyhole trick, their equal fondness for emeralds, and the foolishness of poaching in their woods or pilfering their house. It’s the unnamable all over again.

Rather than trying to repeat the trick, St. Clair takes the opposite tack: full, alienating detail. I’ve just had a batch of Jerusalem artichokes (AKA sunchokes) in our vegetable delivery, and have surprisingly little trouble imagining them grown to gnole-ish size, granted faceted eyes and tentacles, and furious about my recent recipe searches. I also have no trouble believing that my own cultural intuitions are insufficient to help me survive the encounter.

The auxiliary eyes fit right in with the rest of the weirdness. Why not hide said eyes among lesser, larger gemstones? Here the detail is sparse, so we’re left to imagine precisely what an auxiliary eye does, and why it might be compared to a human soul. Maybe gnoles send their eyes out with junior members of the tribe to take in new sights. Maybe they’re the part of a gnole that persists after death, passed down through generations so that vision is inherited along with the more recognizable gemstone hoard.

And if what we still don’t know is as confusing as what we do, maybe you just… shouldn’t touch anything in the gnoles’ house without permission. Or be there in the first place, in service of legitimate commerce or otherwise.

Anne’s Commentary

My favorite thing about writing this blog is discovering writers I’ve never read before, and perhaps my favorite discovery to date is Margaret St. Clair. The editorial preamble to her “World of Arlesia” in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (1950) notes that “Mrs. St. Clair has a special gift for writing about nice, everyday people tangling with the complex—and not always nice—world of day after tomorrow.” I concur! I enjoyed “The Man Who Sold Rope to the Gnoles” so much that I bought a St. Clair compendium and have been bingeing on her stories ever since. [RE: I have fond recollections of “An Egg a Month From All Over,” a childhood favorite that has rendered all my subscription clubs an inevitable disappointment ever since.]

Margaret St. Clair’s biography is like the gnoles’ parlor, everywhere aglint with interest. Her father, George Neeley, was a U.S. Congressman who died in the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919. She earned a Master’s degree in Greek Classics. Her husband Eric St. Clair was a horticulturalist, statistician, social worker and lab assistant, but more importantly he’s likely America’s most prolific writer of children’s stories about bears, about one hundred! World War II saw Margaret assisting on the home-front as a welder. She raised and sold exotic bulbs and dachshunds. She supported the American Friends Service Committee. In the 1940s, she began writing professionally.

She started with detective and mystery tales and tried her hand (as she put it) at “the so-called ‘quality’ stories.” Speculative fiction would become her preferred genre, her publishing niche the 1950s pulps. Of that market she wrote: “I have no special ambitions to make the pages of the slick magazines. I feel that the pulps at their best touch a genuine folk tradition and have a balladic quality which the slicks lack.”

Mention of the “slicks” reminded me of one of St. Clair’s contemporaries, who published in such “high-end” magazines as The New Yorker, Collier’s, Harper’s, and The Ladies’ Home Journal. That would be Shirley Jackson, for me St. Clair’s sister in sensibility. Our readings of “The Daemon Lover,” “The Summer People,” and “The Witch” have shown Jackson similarly adept at sinking “nice, everyday people” into unsettlingly weird situations. Jackson’s fiction lives in the (for her) present, St. Clair’s mainly in the (for her) near future; St. Clair, however, extrapolates from the same real-world trends and anxieties, the same patterns of human transaction.

Jackson and St. Clair also shared an interest in witchcraft. Jackson called herself a witch and immersed herself in what we’d lovingly term suitable tomes. St. Clair was initiated into Wicca in 1966, taking the craft name Froniga. Nor was Jackson a strictly “slick” writer—she also sold several stories to The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction during the same period St. Clair was a frequent contributor.

From the stories I’ve read so far, St. Clair is particularly interested in human transactions involving business and commerce. “An Egg a Month from All Over” imagines a buying club that periodically delivers extraterrestrial eggs instead of books. “Graveyard Shift” centers on the difficulties of an overnight retail worker with eccentric customers and something in the store basement that isn’t just rats. In “The Rations of Tantalus,” the pharmaceutical lobby has won—“happy” pills for everyone! “Horrer Howse” describes an entrepreneurial venture gone way south in its quest to lucratively entertain the thrill-seeking public.

“Rope to the Gnoles” is a pitch-perfect pastiche of Dunsany’s “Nuth” that subtly retains its own dark whimsy and delivers a satirical jab to the “heroic” salesman culture of post-WWII America. I looked for Mortensen’s Manual of Modern Salesmanship and found nothing. No problem. During the first half of the 20th century plenty of similar books were published with such titles as Textbook of Salesmanship; Salesmanship Simplified, A Shortcut to Success; and How I Raised Myself from Failure to Success in Selling. Then in 1952 Norman Vincent Peale’s Power of Positive Thinking appeared. It would become a perennial bestseller and a guide to many aspiring sellers; Peale’s first “rule” is “Picture yourself succeeding.”

Mortensen pictures himself selling rope to the gnoles, which would be no mean sales coup given their reputation for not suffering human visitors to return from their dubious wood. Spurred to a still greater feat of visualization by his success with the senior gnole, he pictures himself securing even the Gibbelins as clients. If you’ve read Lord Dunsany’s account of what happened to the doughty knight Alderic when he attempted to access the Gibbelins’ hoard, you’ll appreciate how o’erweening is Mortensen’s ambition.

This is not to say Mortensen doesn’t have advantages over Nuth and his apprentice Tonker, for they were Thieves and he is a Salesman! He’s a Trader, no Vandal, and he will offer fair exchange for what he takes! He has studied well his Manual and arrayed himself with the desirable Sales Attributes of high ethics, charm, persistence and courtesy! What he’s overlooked is that the Manual deals only with the physio-characterological attributes of humans; what he’s underestimated is how not-human the gnoles are. He’s apparently assumed there will be no communications problems; he finds out mid-sales spiel that his prospective customers are earless and incapable of human speech. To Mortensen’s credit, he’s Adaptable. Luck assists in that the senior gnole does read English. Luck fails in that the gnoles don’t deal in human currency, complicating the issue of a fair exchange.

It is noble but foolish for Mortensen to reject the senior gnole’s idea of “fair.” Given his ignorance of gnole culture—and the exact value of any given gemstone, I suppose—his chances of picking out a suitable downpayment are minuscule, his chances to offend great.

Let’s be charitable. Overexcited by his sale, Mortensen doesn’t think of asking the senior gnole for a more equitable payment in writing, a method of communication that has been working for them. Those two good-salesman attributes he didn’t underline come back to bite him, hard. He fails to realize how tactless it is to take liberties with the gnoles’ cabinets and their contents. He fails to observe the effects of his actions on his customer until it’s too late.

Poor Mortensen. He must know that the ultimate sales goal is ALWAYS BE CLOSING, but he doesn’t close his deal with the gnoles. It says much of his performance, prior to his fatal gaff, that the gnoles do him the unusual honor of not torturing him prior to slaughter, and of executing the slaughter in as humane a manner as possible.

Mortensen probably doesn’t appreciate the gnoles’ tribute to his modern salesmanship. If only he could have lived to see how beautiful his samples looked on his serving platter, all fancily knotted up. Then he could have hoped that the gnoles would send to his firm for more of that cotton cord, cordially mentioning his name as their contact—securing him the coveted district manager accolade, however posthumously.

Next week, we continue T. Kingfisher’s The Hollow Places with Chapters 7-8. We’re through the looking glass/concrete corridor, and now we’re going to find out what’s on all those little islands.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

I admit that I read ahead in The Hollow Places, and I thought I would be irked that Part 4 is not forthcoming but actually this was a delightful review! I love these examples of taking old stories and fleshing them out. Wonderful.

Ruthanna, you mention that one of Mortensen’s failures might not have needed explicit mention “in 1951.” Do you mean there’s something about that era that made people more likely than now to be wary of the screaming?

Not necessarily more than now, but more than before WWII.

Also an addendum: My fond memories of “An Egg a Month From All Over” turn out to have been based on a very fuzzy recollection that preserved nothing except the existence of a club that would let you hatch alien eggs every month. It’s still quite a good story, but I should really be more grateful for the quality control on my international snacks subscription box!

I remember first reading this in elementary school in the anthology “Alfred Hitchcock’s Monster Museum,” (1965) one of several YA fantasy/horror anthologies that Hitch fronted at that time. It really creeped me out, since it presumed the reader knew what a “gnole” was, and they were so unlike any monster I’d ever heard of, and were described so matter-of-factly, that they seemed all too believable.

Those anthologies contained a mix of famous and lesser-known stories by great authors: Sturgeon, Wellman, Bradbury, etc., and were a great introduction for young readers to the giants of the genre.

When I first read that story, I wondered how Mortensen did all his figuring on the back of an envelope (and presumably put all the qualities of the ropes he was demonstrating there too), and also that the Senior Gnole presumably wrote his requirements on it as well. How big was that envelope?!?

Afterwards I had a vague feeling that all Mortensen would’ve had to do was write that the gnole would get much more rope than ordered for that emerald. Enough to satisfy his rope needs for years or decades, probably. I didn’t think of a written promise to pay just like Mortensen didn’t, but then I doubt gnoles have back accounts or that the envelope had any more space

“Pitch-perfect pastiche” it is, indeed! I often have to stop myself from looking for in when thumbing through a Dunsany collection. Thank you for sharing it with us and bringing some well-deserved attention to Ms. Margaret St.Clair.

Oh yes, one other thing. In Nuth, the titular thief and Tonker lay still in the forest for twenty minutes after the apprentice stepped on a stick. Here, the Senior Gnole has no ears. Maybe the Junior Gnoles do.

The Manual of Salesmanship clearly doesn’t hold a candle to Montague Egg’s The Salesman’s Handbook. I’m sure the latter has a clever rhyme to help with sales to mythical beings.

I first encountered this story in some anthology from Scholastic, long before I’d ever heard of Dunsany. Probably Nine Strange Stories, now that I’ve checked its publication history. It has stuck with me ever since.

St. Clair also published under the name Idris Seabright. In fact, that was the name originally on this story. I think, though I’m not at all sure, she used the Seabright byline for stories that leaned more into horror, while St. Clair was more for her science fiction and fantasy.

Now I want to see commenter #9 sell ghostwritten essays to the Gnoles.

It’s a gruesome end for our… hero?…. but it’s hard to view the gnole as the villain. What idiot of a salesman goes into a strange house and start touching things?!

#5 Biswapriya Purkayastha, I think that’s exactly the point. “Don’t be smugly sure of the things you know,” etc.

Anne,

I’m a big fan of Margaret St. Clair, mainly from her novels, and have been trying off and on to find more of her short stories. What is the collection you found? It sounds like it has a completely different selection than The Hole in the Moon and Other Tales by Margaret St. Clair which I found a couple years ago. I had thought that was the only collection of her stories in print, and it’s a good one, edited by Ramsey Campbell, but missing the stories you name.

If you feel like checking out some of her novels, I always recommend ‘The Shadow People’ – the ideas in it are great, despite a slightly weak ending, and I’d argue for it as the first ‘urban fantasy’ of the modern form, or one of the first, blending magic-and-elves fantasy and near-present dystopian SF.

Following the breadcrumbs you dropped above, Anne, I’ve procured myself this, and read the first three:

A Compendium of Margaret St. Clair (Giants of Sci-Fi Collection Book 1)

I was going to ask the same as my fellow commentors above: I know of St. Claire, but this story had me so in stitches that I have to have more.

I’m also so glad to have read the Dunsany last week. Besides realizing I’ve been thinking his name was “Dun-a-sey” for years, it also gave me the metatextual appreciation of this story. I love storytellers in conversation, exploring their influences. It’s such a hallmark of Weird in particular, but this is so much better than just mentioning Unaussprechlichen Kulten and calling it a day. That this story also says a great deal about the 50’s and capitalism is all the more impressive. As an aside, the VamderMeer’s The Weird is one of the best book purchases I’ve ever made, on this column’s advice.

I’m reminded of the story I heard of a young, just starting out, door to door salesman being asked by a more experienced one what was the most important thing to concentrate on in making a sale?

“The product!” says the naive youth.

“No,” says the voice of experience. “It’s the customer. Always focus on the customer. That’s how you make a sale.”

Or notice you are about to be made into dinner.

By the way, there was an article about markings from lizard hands on ancient cave paintings in the Sahara. Scientists, who obviously don’t read Lovecraft, are wondering why the people-who-must-have-been-human who painted the caves put them there.

https://www.livescience.com/53944-prehistoric-rock-art-nonhuman-hands.html

Next week, we continue T. Kingfisher’s The Hollow Places with Chapters 7-8.

Did I miss chapters 5 & 6?

@18 – Here’s the post for chapters 5 and 6. (And the index for the series is here.)

Thanks, oldfan!

@18

I missed it as well. It never appeared when I did my daily visit to this site. Not had that happen here before. And I’m in the habit of scrolling back for a week to check on new comments. Not had that happen here before.